As architects we strive to maintain a

professionally independent and holistic view of the process of architecture.

This is to serve and assist the local and larger communities within which we

operate. Codes of conduct set out by governing bodies such as the ARB reflect

this aspiration but serve only as a minimum standard of behavior expected of

those using the title of architect.

The architect, like the client they work

for and all those who will experience a built piece of architecture, belong to

a community that informs and shapes its own physical environment. All of us are

engaged in this process of creation, whether we are aware of it or not. On an

individual level, our own cognition and perceptual processes fuel our personal

and subjective experience of architecture. Our thoughts, belief systems and

cultural ideologies weave a complex and intricate web of perceptual filters

that interprets an external reality into subjective experience. Our behaviour and

the way we respond are extensions of this experience. This process is the way

we exchange ideas with our environment, thus shaping it. It in turn shapes us, continuing

a complex reciprocal relationship.

This model of experience illuminates architecture

and our physical environment not as inert spaces that we occupy but rather spaces

created by our occupation.

It is an intimate and cyclic relationship between people and space, human

communication and architecture. Our environment is inseparable from the way we

perceive and use it.

This insight leads us to realise we are

ultimately responsible for our own experience. We are continuously constructing

our own realities and creating our environment. The polymath Gordon Pask recognised this intimate relationship we have with our environment describing the

interaction as a conversation, operating with the same mechanics as a dialogue does

in language. To Pask communication and

conversation differ. Communication is a linear process of information going

from A to B, in a rather passive way. Conversation operates at a deeper level, is

participatory and active. It is a looping, recursive and iterative process

between two or more cognitive systems, distinct perspectives or individuals. Most

importantly conversation requires understanding and agreement over the concepts

and ideas, which are shared between individuals. The result of conversation is a

new perspective to both individuals.

Pask considered architecture as one of

the fundamental conversational systems in human culture and that we are

observing beings who construct our view of the world by interacting with it

through conversations. With this perspective Architecture reveals itself as a time-based

phenomenon, which relies on the unique construction of the observer. Viewing

architecture in this light begins to place the architect in an interesting

position not simply as designer of physical form and aesthetic but as system

designers, designing systems that grow, develop and evolve. A building is a living entity, a system which

operates within a larger system (e.g. a city, human society) and it is these

larger systems that the architect also designs.

A conscientious architect, like Pask,

cannot view a building in isolation but will consider the wider context

(physical, social, cultural etc.) with the deeper understanding that a building

is only meaningful as a human environment. Our built environment is

simultaneously serving us and influencing our behaviour.

Our buildings are not static but are growing, living and evolving. As an

architect it is imperative to recognise our role and responsibility in the

development of our society’s conventions and traditions.

We are becoming more aware of the

importance for architects to design with provision for unknown future uses and

the evolution of a design. The ecological crisis that we are currently facing reflects

our civilization’s avoidance of meaningful conversation with the natural

environment. Ensuring our built environment converses sensitively with the

ecological cycles that govern our planet is an urgent activity that all of us

share responsibility in. As architects, city planners and engineers we are in

fortunate positions that our professions can make a significant impact within

these conversations.

Our cities will survive long after us

and will carry with them our intentions and negligence for future generations

to inherit. Buildings, which are ill conceived lack consideration for their

entire lifespan and fail to recognise the interconnectedness between our cities

and our wellbeing. A built environment that is conceived to be static and

non-conversing perpetuates social division, financial deprivation and

ecological instability.

The architect is an enabler of

conversation; not only between buildings, their inhabitants and the natural

environment, but also between the numerous forces and mechanisms, which shape

and influence the built domain. Clients, stakeholders, consultants,

politicians, planners, contractors, public user groups, heritage and

conservation groups and numerous others must all converse effectively with each

other and themselves to achieve common goals that are beneficial to all. This

is often a difficult process. Shared and common objectives are often ill

defined, lack wisdom and holistic thought. Short-term economic and political

agendas all too often take over a conversation reducing it to one-sided

communication. The architect has a duty to maintain professional independence

within this process. He is to ensure integrity whist providing a service for

his client, but also remembering the higher service to the larger conversations

of our cities and planet. Considering the wider context within which we build and

ensuring conservation is one of the most fulfilling aspects of architecture, bringing

more meaning and depth into our work. Sharing this outlook with our clients,

and all those involved in building procurement is essential, as is being open

and receptive to the ideas and perspectives that others also bring to the

conversation.

There have been many architects who have

recognized architecture as a dynamic process, which is given meaning by its

occupants. The visionary architect Cedric Price, who would have been involved

in discussions with Pask at the Architectural Association, explored architecture’s

potential to nurture conversation. Price, although building very little in his

life became one of the most influential architectural thinkers of the last

century. In a series of unrealized projects, Price presented architecture as a

dynamic process between user and building.

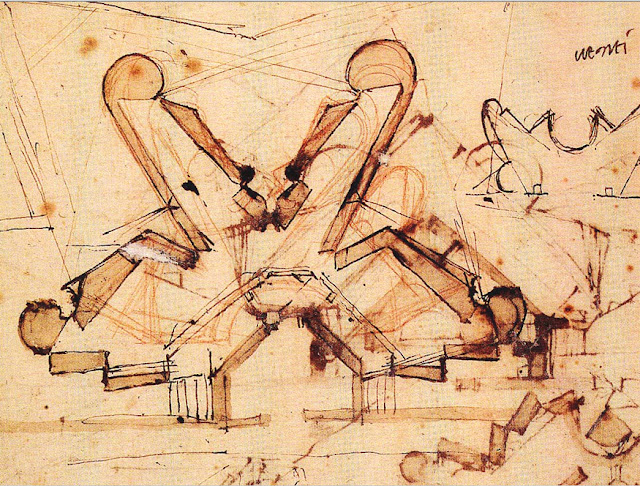

Fun Palace (1961) in collaboration with

theatre director Joan Littlewood, embodied conversational philosophies, and

sought to provide a building that was defined by the changing desires and needs

of the users. The project embraced optimism for current technology to provide a

flexible and responsive architecture. Consisting as a kit of parts, a

structural grid of steel lattice columns and beams provided a frame within

which dynamic elements such as hanging theatres, activity spaces and cinema

screens could be assembled, moved and taken apart as required.

The result was playful, free spirited proposal defined by the activities of the

users. Focusing in on the time based nature of architecture paved a way for

subsequent architectural thinking and expanded the potential of architecture as

a social catalyst.

|

| Plan of the Fun Palace illustrating dynamic elements |

Buildings such as the Pompidou Centre in

Paris clearly echo philosophies of Price’s work. Rogers and Piano’s competition

entry was the only scheme to divide the Beauborg site into two halves, with one

half being entirely given over as a public piazza. The building itself strived for an inherent flexibility

through spacious floor plates uninterrupted by services and vertical

circulation. The strategies employed recognise conversational ideologies by

placing human activity at the heart of the scheme. The public piazza, which

continues to attract performers, museum goers, and a multitude of public life,

has served to regenerate and revitalize a once forgotten part of Paris. The

users of the piazza continually re create it through occupation and use. This

conversation between inhabitants and environment becomes an enjoyable spectacle

in its self, which in turns attracts more users. A successful public realm such

as this is a place for the city to become aware of itself.

|

| The city becoming aware of itself at the piazza of the Pompidou |

In London, Denys Lasdun (who also worked

with Cedric Price) designed the National Theatre at the south bank, which can also

be seen as a functioning conversational system. One of the great successes of

the National has been its dynamic dialogue with the public. The building’s

concrete landscape provides large floating terraces which serve to reconnect

the site to different parts of the city, such as providing access from the top

of Waterloo Bridge to its underside, and offering intimate views across the

Thames. This increased connectivity facilitates pedestrian movement encouraging

human interaction. This increased animation allows the terraces themselves to become

stages for public life. Often the events outside of the building, such as the

recent Inside Out festival, are as popular as those that are contained within.

|

Floating terraces and public realm weaves in and out of the National Theatre allowing external performance spaces to emerge

|

Recognising architecture as a dynamic

process, operating as a conversational system makes it impossible to view a

building in isolation. Often a client

will make a set of stringent demands based on financial and political

imperatives. If these obscure a holistic perspective of how our buildings will

operate within the larger context, then our architecture will fail to participate

in meaningful conversation, perpetuating social disparity and ecological

imbalance. As architects we have a civic responsibility to ensure our buildings

are capable of such conversation and have the potential to empower human

activity.

Paul Pangaro, Cybernetics and

Conversation, 1996